The Champions League returned in mid-week with the first legs of the final qualifying round on Tuesday and Wednesday. Unfortunately, the draws pitched together a number of strong teams that could have a big impact on the competition, who would now have to battle over two legs to reach the group stages. Fortunately, this gave PR, AL and JD interesting ties to analyse, and each author summarises the key aspects in the clash they watched.

Sarri’s side in dominant win

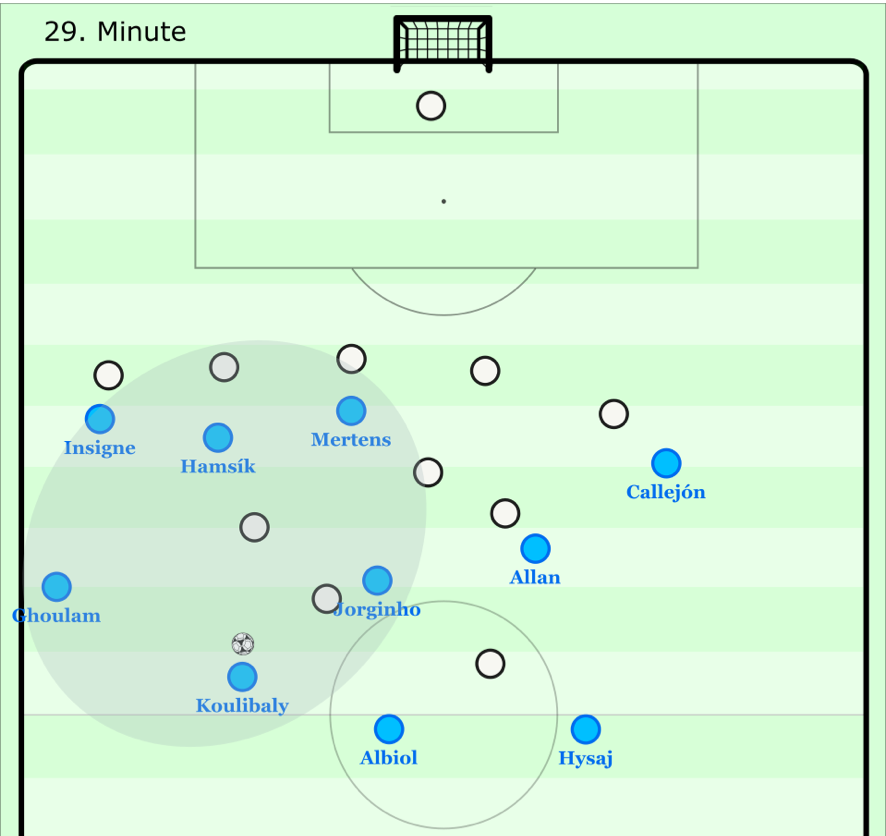

From an asymmetric 4-3-3 with a narrow structure, particularly oriented towards the left sector, the Italians were able to have a stable build up. With the back line having close distances between them, they could circulate quickly against Nice’s passively centre-focused forwards. Ghoulam, the left back, had more freedom to move higher in the pitch overloading and giving a passing option to connect after the switch in a first moment. He was also able to manipulate Jallet through his movements thus creating exploitable spaces at times for Insigne or Hamsik.

The three midfielders played between the lines overloading the left sector particularly, and attacking aggressively with great mobility the spaces behind the opposing midfielders. Particularly in the attacking left halfspace, they gave vertical passing lines for the centre-backs and each had near support to make quick one touch combinations. The close distances between them and the support at times of the forwards created the connections from where the central combinations arose.

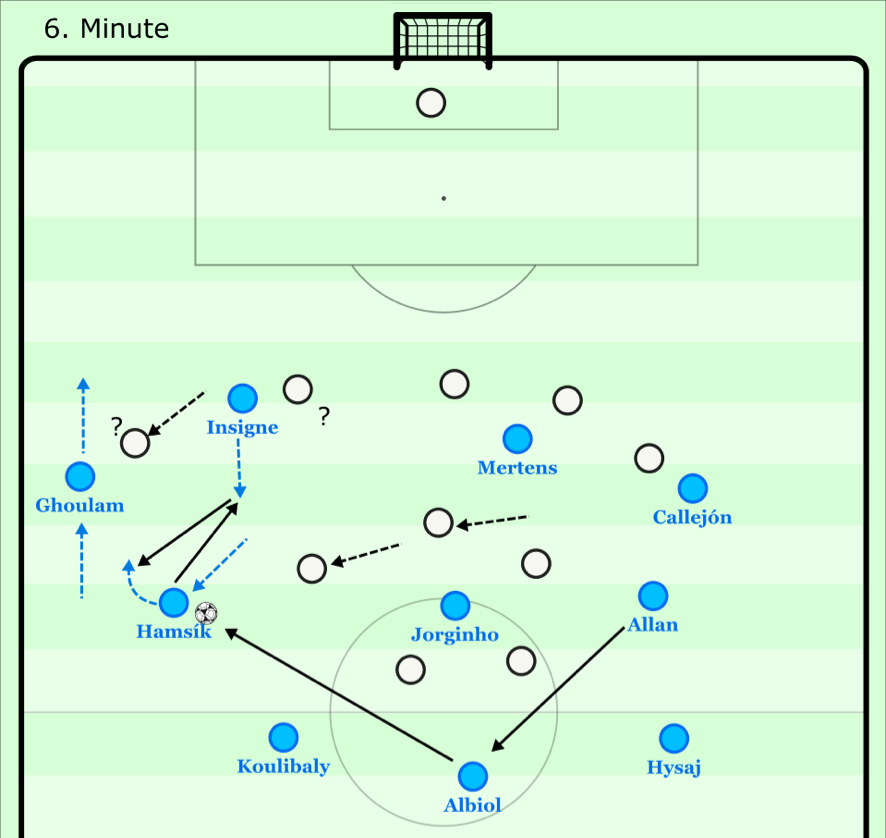

In the starting first quarter of the game, Nice’s 5-3-2 mid-block was easily manipulated by Napoli’s right to left circulation in the first line, in the process creating a free man in the left halfspace. In that sector, Nice’s defensive structure was completely unbalanced due to the lack of access from forwards and the deep position from Jallet, therefore Koziello was unable to deal with the movements and combinations between Hamsik, Ghoulam, Insigne and Jorginho borne out of the aggressive vertical passing from the centrebacks.

The created dynamical advantages were followed usually by a quick pass to the forwards attacking the space behind the defense or playing outside to Insigne and at times Hamsik or Ghoulam. From here Sarri’s men were able to create a dynamical advantage through the provoked manipulation of Nice’s defenders, by their movements dropping and running through the halfspace.

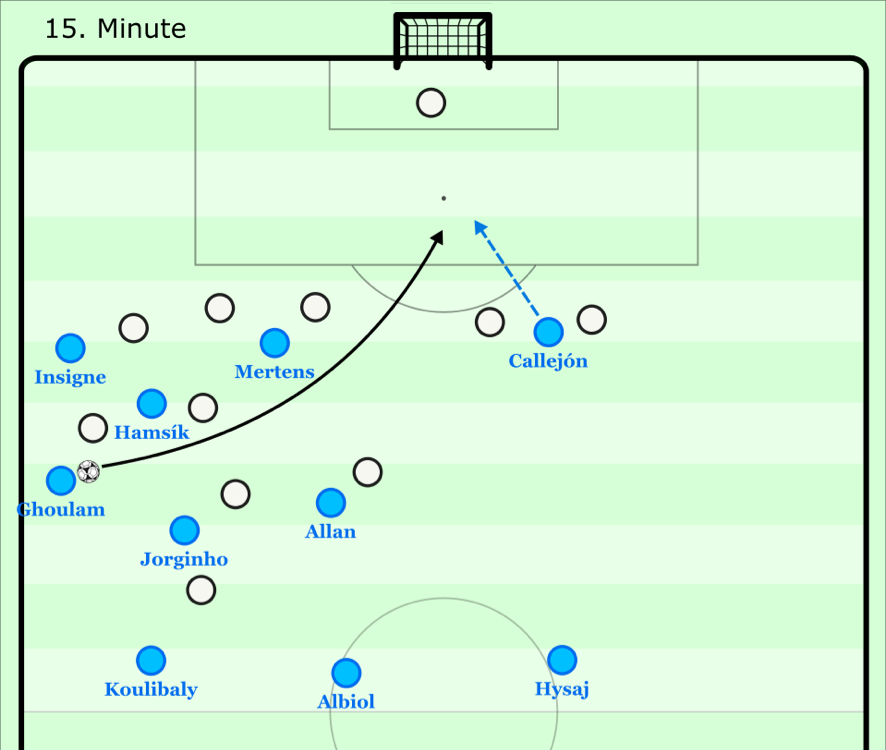

Due to the height of the defensive line of Nice, the vertical runs by Napoli’s forwards behind the last line were very successful and easily exploited. Napoli mixed the short and quick combinations in the left sector, with more direct passes behind the last line towards Mertens and Callejon’s runs well. From one such situation they scored the first goal.

The forwards were willing to create many runs behind the last line when Nice tried to hold it high. However, they were also able to drop deep to give passing options overloading the centre to have more connections in the combination play.

After the goal, the visitors dropped deeper trying to block the depth runs from forwards. In this context Italians were able to execute a more horizontal possession moment in the last third but keeping the characteristic combination play and overloading the left sector. They were especially successful with the diagonal and chipped passes to the box targeting usually Callejon’s well timed runs through the right halfspace, after attracting the opponents (in position and attention) to the left sector.

Callejon’s runs were usually effective due to the positioning in the blind side of Le Marchand and the timing of the runs along with the group manipulation provoked by the overload in the left sector explained before. This allowed Callejon to manage the timing and direction of the movements along with a threatening diagonal passing lines from the midfielders.

Later in the first half Napoli players started tying also to exploit direct central combinations since the central defenders were even less challenged and thus trying to create quick vertical passing options and layoffs to penetrate the French defence. The overload in the centre with the three midfielders and at least two forwards manipulated Nice, provoking their midfielders to press. This enhanced the situational advantage that allowed Napoli to create successful depth dynamics, and also to counterpress effectively if the ball was lost.

Furthermore, the Italian dominance wasn’t limited only to the possession moments. Without the ball, even if not displaying an avant-garde sophistication, they executed a rather effective high pressing orienting the circulation (within a poor build up structure indeed) through Nice’s left centreback forcing long direct balls which were intensely challenged and usually recovered in the second ball or picking the rebound. Along with their strong counterpressing due to the style of the attacks and dynamics in their combination play, Napoli shut down almost every possible attacking option from Nice. In fact, the French players were able only to create a few chances from recoveries after ball loses from Napoli.

A final note on Napoli’s strategy

The offensive strategy was consistent in forcing/provoking the press in the vertical axis rather than in the horizontal one with the first line (with the Italian team’s back four) This creates a very stable build-up, avoiding being underloaded. Since the opponents are not going to get easy access, they push forward which creates space either behind the last line or between the lines. This is combined with a structure that has several players between the lines, allowing for quick vertical combinations and progressions through dynamical advantages, and also connecting passes to the forwards running behind the defence.

Apart from a stable and more horizontal possession moment in the first line before passing the ball to the midfielders, the attacking process of Italians was rather vertical and risk oriented. They attempted to get a depth option in the same sector where the attack takes place as quickly as possible, thus avoiding the use of unnecessary horizontal shifts or backwards passes to re-start the sequence in a controlled way. Instead, the midfielders and forwards made quick and short movements to manipulate and then exploit the dynamical advantages created behind the last line or direct passes into the box.

Celtic too strong for Astana

Celtic flew to a 5-0 lead against Astana on Wednesday night in the first leg of their crucial Champions League qualifying play-off tie. Despite a messy start to the game, where neither team looked in control, Celtic were eventually able to assert themselves, blowing the Kazakh champions away in an extremely assured performance.

Initial stages

Astana started the game engaging Celtic high up the pitch in a bid to disrupt their rhythm. Celtic’s usual rotation from a 4-2-3-1 to a 3-2-4-1 (led by Tierney’s advancement from left back) saw them build up with a clear 3-2 structure in the first lines. Astana’s 4-3-3 gave them good pressing access to players across this structure, making it relatively easy to dissuade central progression, thus forcing Celtic to the flanks. Man-orientations on the ball-near side made breaking through this flank-pressure uncomfortable. This, coupled with ball-far players indenting to maintain access and providing decent spatial coverage, made it easy for Astana to regain possession after long passes or clearances.

The away side compounded this pressure on the Celtic back line through their direct approach. A couple of clipped passes into Kabananga up front early on were well supported by Astana players – both from behind and from the side – giving him the ability to lay off to a teammate or for a number of players to be involved in retrieving the second ball. From these initial direct incursions, the Kazakhs could establish themselves in the Celtic half and bring their dynamic wingers into play.

As the initial chaos subsided, Astana started to allow Celtic possession slightly higher up the pitch. When in this medium block, the visitors engaged around the halfway line, set up more often in a 4-5-1 shape as opposed to a more commonly seen 4-1-4-1. Celtic struggled for large portions of the first half to break through this midfield wall, due to the enhanced horizontal coverage afforded to the away side through this structure. With more players in the midfield chain, the horizontal distances each of them were responsible for was reduced. This led to a number of attempts to play passes between players in the line of five being intercepted, in turn leading to dangerous counter attacking opportunities.

Even when these passes were completed (usually to Sinclair through the left halfspace), Astana were initially able to prevent any further progression. A reception between the lines was usually met with a centre-back stepping out to aggressively press the receiver, the midfield line intensely collapsing back towards the ball, and occasionally the central midfielder of the five, Maevski, who would situationally drop slightly deeper to maintain access to any players looking to move behind the midfield.

The result of all this was a period of play – roughly 25 minutes long – where neither team was able to make significant inroads through organised phases. Due to Astana’s fairly strong compactness, Celtic struggled to gain control of possession in their opponent’s half – unable to form strong structures around the ball due to their lack of control in progression, unable to gain control due to their lack of strong structures in possession to support their counterpressing.

Celtic gain midfield control

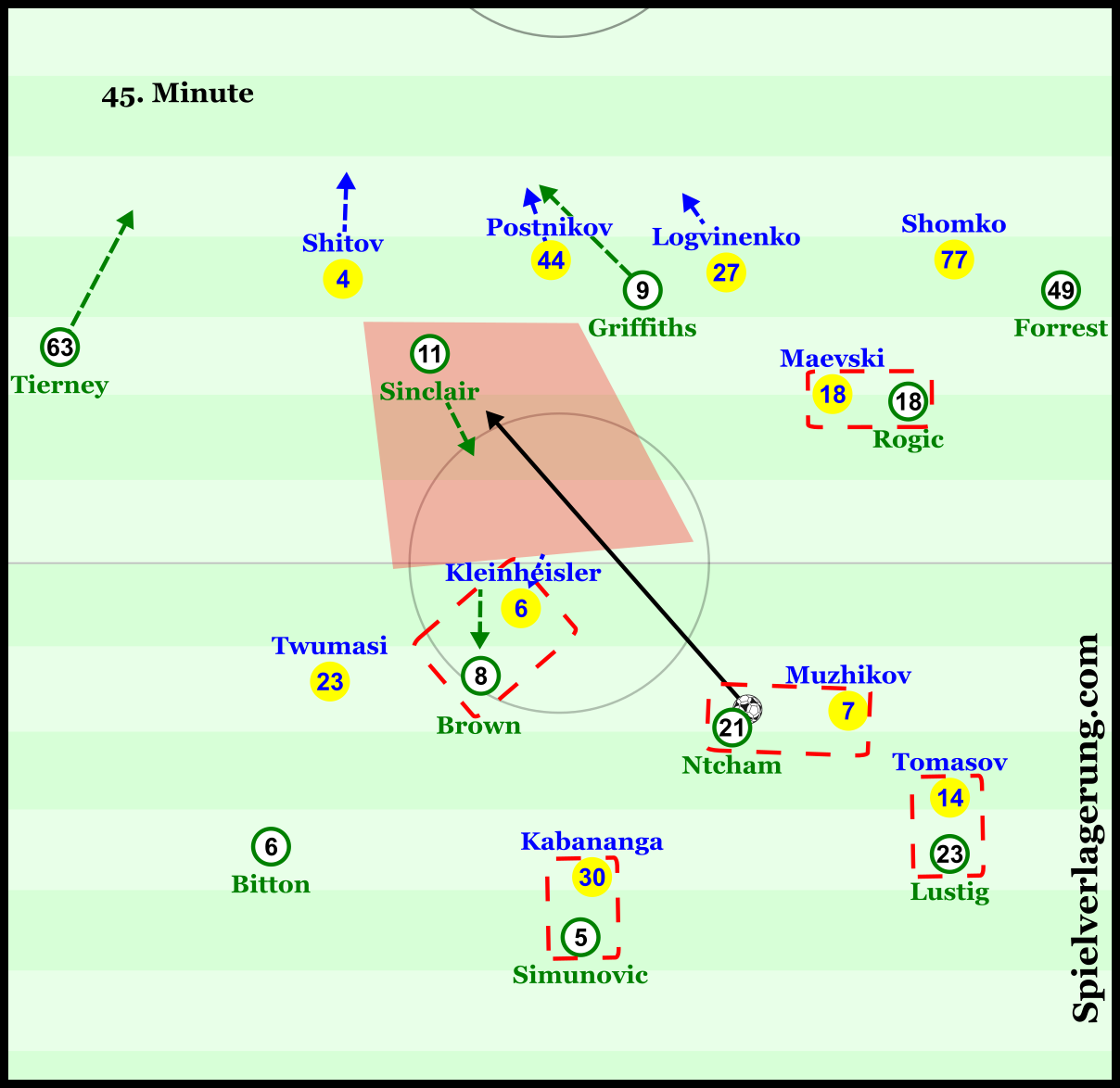

Celtic eventually managed to settle the chaos of the opening minutes through their midfield dynamics. Captain Scott Brown made frequent dropping movements from around the 30-minute mark to the left-back position opened by the advancing movement of Kieran Tierney. Due to the slight man-oriented behaviour of the Astana eights, this had the effect of bringing one of them out of the super-compact midfield that had blocked so much of Celtic’s central advancement in the early stages.

Brendan Rodgers’ side coordinated these movements well, giving them maximum space between the lines to attack from. When Brown tilted to the left-back area, Ntcham would make a slight, mirrored movement on the right side to the same effect. If these players could attract Astana’s eights whilst making these movements, a large space was opened for Sinclair to move into. While Rogic’s drifting to the right side – allowing Sinclair to indent into the left halfspace – is a common occurrence in this Celtic side, the further space-opening movements from the sixes destroyed Astana’s previously strong midfield coverage.

Furthermore, Celtic were able to prevent the defensive line from pushing up to maintain compactness. Leigh Griffiths was instrumental in this respect, with his constant depth-seeking runs providing considerable problems for the Kazakhs, as they struggled to cope with his pace. Occasionally joined by Sinclair, the striker found great success running into space behind the back line that they left as they tried to stay vertically compact. The result was either a further opening of the huge space between the lines if they tracked his runs, or a massive area behind for Griffiths to run into if they didn’t.

Griffiths’ influence, though, was not merely reduced to destroying vertical compactness. When Celtic have the ball on the right side, Forrest’s natural inclination to position himself on the touch line, and not right on the last line of the defence, invites the opposing left-back out of the defensive chain to press him, while Griffiths positions himself in between the centre-backs in a fairly central position. In these situations, the ball-near centre-back is reluctant to shift to cover his full-back, for fear of leaving a direct lane open for Griffiths. This has been a common scene in most Celtic games this season, though Rogic’s goal was a rare example of the Australian using this space to break through into depth.

Conclusion

As far as European performances go, this was certainly one of Celtic’s most mature. A low-risk approach – while still managing to pose some threat through Griffiths’ running – when the guests tested the back line, and their wrestling of control & organisation from the hands of chaos made Brendan Rodgers’ side good value for their comfortable win.

Clash of the 3-chains in Hoffenheim

Klopp’s plan

In his pre-match press conference, Klopp stressed that Liverpool “know everything” about their opponents. For the viewers then, it would be interesting to see how this knowledge translated into a game plan. With Liverpool’s narrow 4-3-3 pressing shape up against Hoffenheim’s 3-1-4-2, the key question was how Liverpool would prevent the wing-backs receiving in space, whilst having access to the back 3, and covering the defenders against Hoffenheim’s attacking midfielders, and strikers.

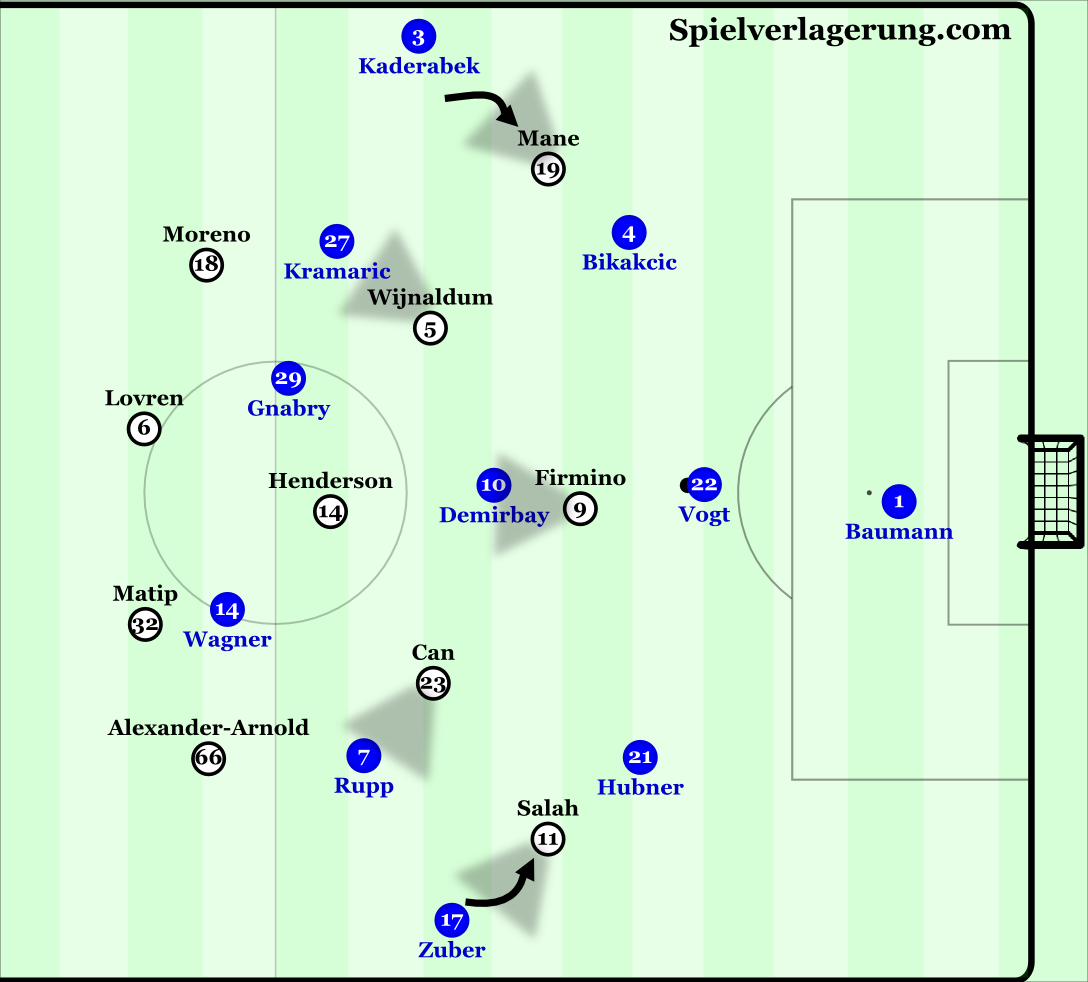

To create access against Hoffenheim’s defenders, whilst blocking the wing-backs, Salah and Mane would press the ball carrying side back with a curved run to cover the lane to the ball-near wing-back and force the German side into the compact centre. In higher pressing, Liverpool’s ball-far 8 would stay higher to man-mark Demirbay (Hoffenheim’s defensive midfielder), whilst the ball-near 8 and Henderson would move across and block passes into Hoffenheim’s attackers. In these situations Firmino could press Hoffenheim’s first line, often forcing them back to Baumann.

In midfield pressing however, the responsibility for blocking Demirbay fell to Firmino, who would move deeper when Hoffenheim’s side backs had the ball. This meant Liverpool weren’t able to block re-circulation, since Vogt (the central centre back) was constantly available for a back pass to relieve pressure. Uncharacteristically, Klopp’s men spent large periods with a high focus on blocking passing options, and little or no pressure on the ball carrier.

Hoffenheim’s routes of progression

Due to the little pressure on them, and Liverpool’s focus on blocking passing options, the Hoffenheim defenders had to dribble to manipulate and open passing options. To progress against Liverpool’s 4-3-3, the key was challenging the decision/positioning of Firmino and the Liverpool 8s, who had to focus on blocking re-circulation via Vogt, blocking Demirbay, and blocking Hoffenheim’s large presence between the lines. Based on the decisions made by Firmino, Can and Wijnaldum there were a number of different ways the home side were able to progress;

- When Liverpool’s winger pressed with a curved run blocking the near wing-back, and Firmino stayed deep to block Demirbay, Hubner or Bikakcic could return the ball to Vogt in the centre who could then play diagonally into the nearby wing-back.

- When Salah or Mane pressed the side backs with a curved run, and Firmino blocked the back pass to Vogt, Hoffenheim could play into Demirbay, who could play into the open wing-back.

- When the ball carrying side back was pressed with a curved run, Firmino blocked the back pass, and Liverpool’s ball-near 8 moved up to block Demirbay, they could play into the open channel between Liverpool’s pressing 8 and winger, using one of the forwards for a wall pass into the open wing back.

- When Firmino moved up to block Vogt, and the ball carrying side back couldn’t progress, Vogt would move higher and form a double pivot with Demirbay, opening the back pass to Baumann and allowing the German side to re-start their build-up. Alternately, Vogt could receive the ball behind Firmino, if the Brazilian moved in anticipation of the back pass.

Hoffenheim’s attacks

Whilst they dealt impressively with Liverpool’s pressing, and were able to progress into dangerous areas regularly, Nagelsmann’s side didn’t often arrive in the final 3rd with good conditions to create chances. When Hoffenheim progressed, it was usually through passes into the forwards behind Liverpool’s midfield either from the centre, or from the wing-backs. Of course they faced high pressure in this space, so they had to combine quickly to bypass the pressure.

However, too often these combinations were from static positions, without runners clearing space for the player on the ball to dribble forwards. Therefore, they often combined without gaining space, and Liverpool were able to regain their defensive balance through recovery runs.

Part of this was due to how efficiently Liverpool defended these situations. When Hoffenheim played into their forwards diagonally from the wing-backs, Liverpool’s defenders pressed whilst directing them back towards the wing. This is a factor in Hoffenheim’s inability to move these combinations into dangerous areas.

Liverpool’s asymmetry and adapted roles

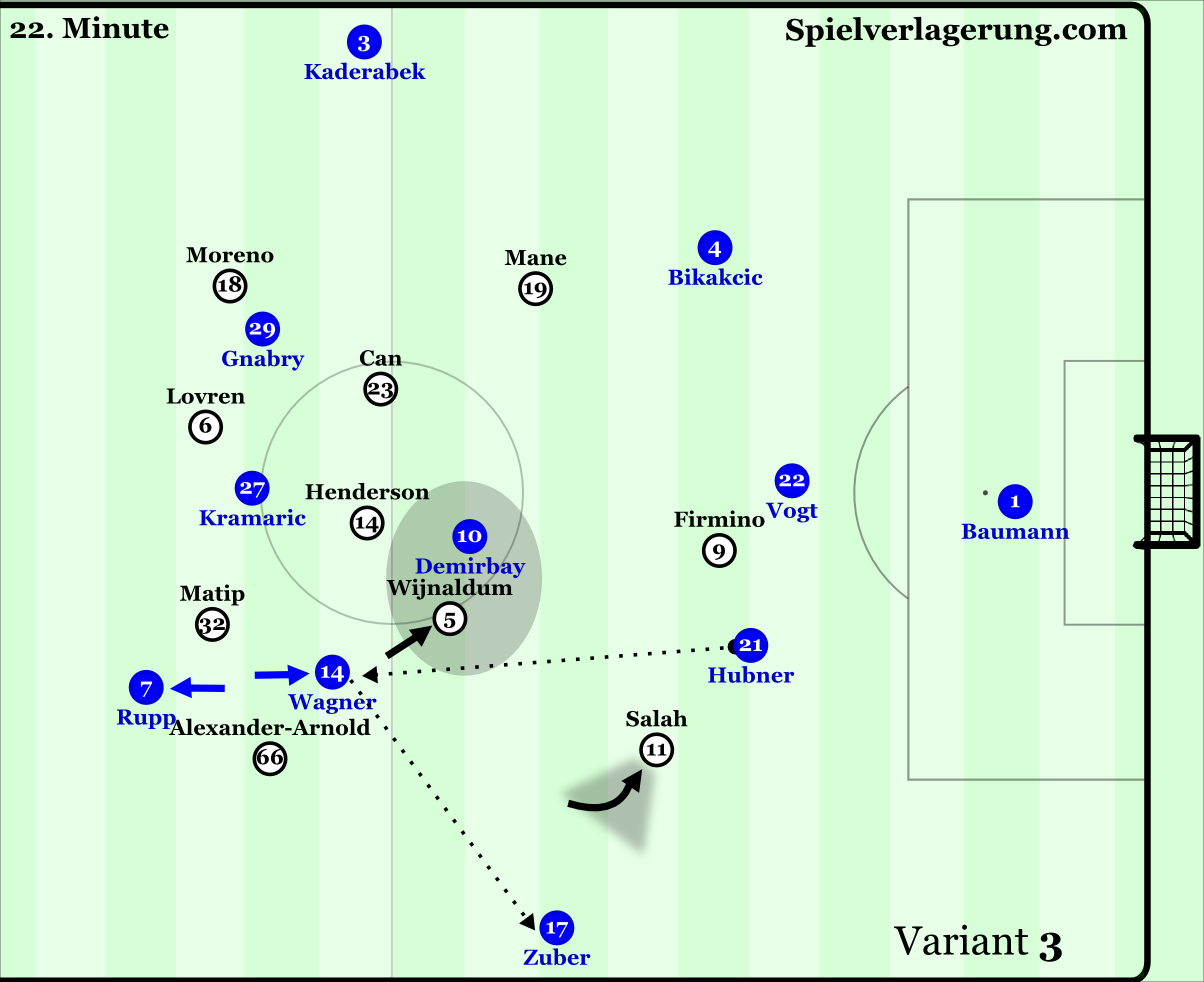

An interesting adaptation from Klopp’s side was the positioning of the full backs and wingers. Liverpool typically play with very high and wide full-backs, and very narrow wingers creating a combinative front three. However, against Hoffenheim’s 5-3-2 defensive structure the positioning was tweaked to exploit the spaces Hoffenheim leave open.

In the 5-3-2, the midfield and forward line are very narrow, whilst the defensive line can cover large width. Liverpool’s typical structure has huge width on the last line (advanced full-backs) and are narrow in the defensive and midfield lines. This creates a 2-3-5 in possession, and this would theoretically give Hoffenheim’s 5-3-2 natural access to every line of Liverpool’s structure.

To counter this, Liverpool used Alexander-Arnold deep and narrow, creating a back three alongside Lovren and Matip, whilst Moreno had a more typical role on the left. With the young right back positioned deep and narrow, Salah would play high on the right touchline.

Alexander-Arnold’s positioning had big effects in two particular phases. By creating a back three in the away side’s early build-up, they could outnumber Hoffenheim’s front two, and the young right back was often the free player to start Liverpool’s build-up in the right half space. From here he could drive forwards and attract one of Hoffenheim’s midfield 3 to press, freeing one of Liverpool’s midfielders to receive the ball.

Secondly, when Liverpool had the ball on the left side, the young right back would be free in the right half space (due to Hoffenheim’s narrow forward and midfield lines) to receive a switch. He could thus use the space ahead of him to drive forwards, advancing the ball deep into Hoffenheim’s half. In these situations Salah’s positioning high on the right touchline, helped in pinning Zuber back due to the threat he could pose running into any space left behind.

When reaching Hoffenheim’s box, Alexander-Arnold would pass into the Egyptian winger, and either over or underlap him creating varied situations for Salah’s dribble.

Halfway Conclusion

A high class encounter finished 2-1 to the away side, making Klopp’s men the favourites to progress to the group stages. The adaptations to the structure of the opponents was clear from both managers, and it will be interesting to see what changes and what remains for the 2nd leg.